Back in October I wrote a post about our mash tun, and how we “mash” grain to make fermentable wort. So I thought I’d continue by describing the boil process.

Boiling sterilises the wort, extracts bitterness from the hops and develops rich toasted flavours. Generally we boil for an hour using a Baby Burco that I bought on eBay, although some beers require a longer, 90 minute, boil.

So let’s start. After we’ve run our wort out of the mash tun (see the previous post), we transfer it to the Burco:

The Burco is then turned on. As you can see (below), the wort produces quite a lot of foam to start with. We’ve had the odd boil-over because of this which is horribly sticky, so we generally watch it like a hawk at this stage.

Hops are added at various stages during the boil. These impart three things to beer: bitterness, flavour and aroma. To extract the bittering oils from hops they need to be boiled for a full hour. The problem with this is that the more volatile flavour and aroma chemicals are driven off during this time, so additional hops are generally added towards the end of the boil – often at 10 minutes before the end (for flavours) and a couple of minutes before the end (for aroma).

Hops can be bought in a number of forms: loose, compressed vacuum sealed and compressed pellets. Our hops come vacuum sealed and compressed, and look like this out of the pack:

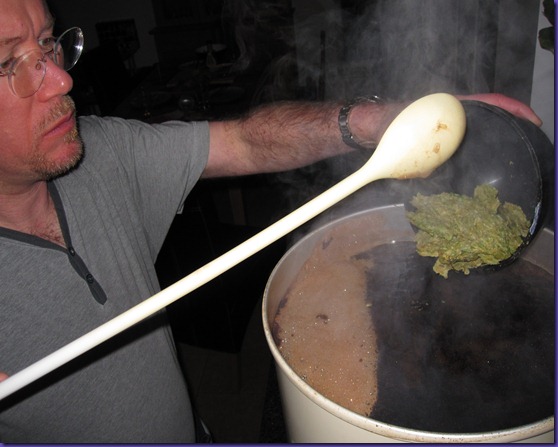

After carefully weighing them they are added to the boiling wort:

The wort is boiled vigorously, which as you can see below requires careful monitoring. We generally drive off 15-20% of the water as steam – notice the way the wort has dropped down from the original scum line. Notice also how vigorously the wort is churning – it needs a good rolling boil:

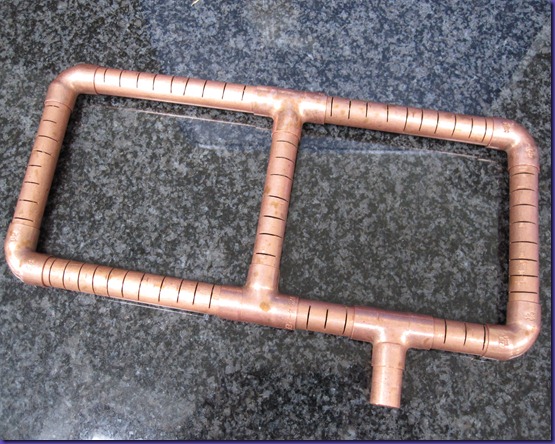

At the end of the boil the wort must be cooled to room temperature to allow the yeast to be pitched in and the fermentation commence. Cooling takes a hell of a long time, so it was not long before we invested in a wort chiller, which allows cold tap water to be circulated through the wort:

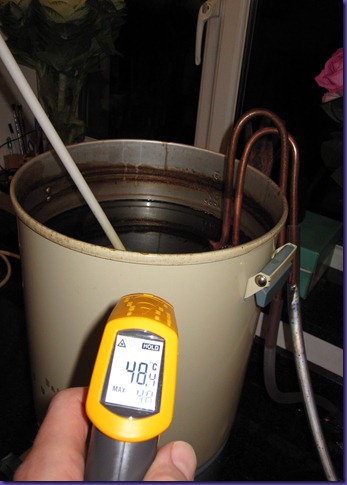

Crash-cooling the wort in this way has another advantage in addition to saving time: it creates the “cold break”, which is the precipitation of some of the proteins in the wort. This happens at about 50C, and you can see little strands appear in the wort that look rather like Chinese egg soup. Getting some of the proteins out of the beer helps prevent hazy beer.

During cooling we monitor the temperature:

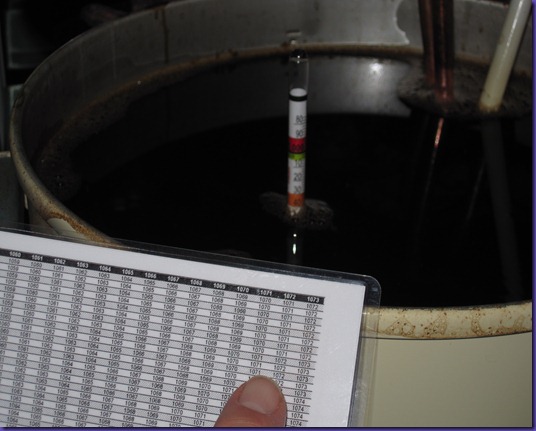

We also check the specific gravity (density). The denser the wort, the more sugars it contains, and the stronger the final beer will be. The density of the wort will be affected by the temperature (it gets less dense the hotter it is), and since our hydrometer is calibrated to be accurate at 20C we use some conversion tables I made to allow us to correct for the temperature.

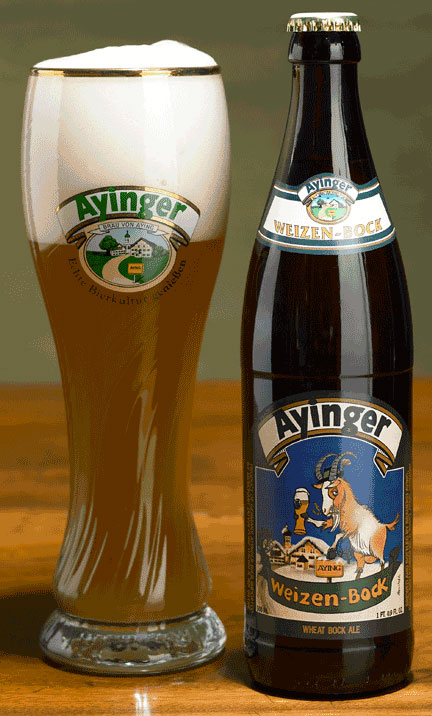

Back in the old days beer pump clips and bottles used to state the “Original Gravity” (OG) of the beer. If you remember back to those days you may have seen Marston’s Pedigree as 1.043, Theakston’s Old Peculier as 1.058 and Marston’s Owd Rodger as 1.080. This gives a guide to the strength of the beer, but it does depend on how much residual sweetness there is in the beer. Two beers with the same OG may contain considerably different amounts of alcohol if one is very dry and the other very sweet. This is why these days beer strength is required to be quoted in Alcohol By Volume (ABV), which takes into account both the starting sweetness and final sweetness.

The boil is complete and the wort just needs to be transferred to the fermenting vessel and the yeast pitched in. This stage is the only stage in beer making where the beer is treated roughly. Under all other circumstances you really need to avoid dissolving oxygen in the beer, because of the resulting oxidation and the off-flavours it produces. But to get the fermentation started you need the yeast to multiply. This reproduction needs oxygen and the boiled wort will have very little in it. So at this stage and only this stage, the beer is splashed about a lot to ensure plenty of oxygen dissolves. The way we do it is to pour the wort from the Burco into the fermenting vessel from a height:

So that’s it. In goes the yeast and the beer (for once the yeast goes in we stop calling it “wort” and call it “beer”) is moved to a relatively warm place (18-20C) to ferment. Om nom nom.